Macroevolution of the suboscine passerines

Most of my current research involves questions about macroevolution in the suboscine passerines. This is one of dominant groups of passerine birds in South America, where they have diversified into a wide variety of habitats, from deserts to rainforests, and from sea level to the highest mountains. They comprise about 1,300 species, and occupy a broad diversity of niches that are occupied by the oscine passerines elsewhere in the world. I am interested in how this diversity came about, both the diversity of species and the diversity of traits. In collaboration with researchers from many instituions I have compiled a species-level database of phylogenetic, distributional, song, plumage, morphometric, and ecological data from all species of suboscine passerine birds. This is an active area of research, and if this research interests you, either as a student or a collaborator, please reach out. Below, I have outlined two current research projects using these data, but there are many additional avenues of research that would be fruitful.

This work is in collaboration with the following researchers, and I encourage anyone interested in this topic to look into their research as well. Joseph Tobias at Imperial College London, Gustavo Bravo at the Instituto Alexander von Humboldt, Santiago Claramunt at the University of Toronto, Elizabeth Derryberry at the University of Tennessee Knoxville, Robb Brumfield at Louisiana State University, Rafael Marcondes at Rice University, and Michael Harvey at University of Texas El Paso.

Tradeoffs in sexually selected traits

As far back as Charles Darwin, researchers have noted that species of birds that sing complex or loud songs often have "dull" plumage, and vice versa. This idea is often termed the Transfer or the Trade-off Hypothesis, with the idea being that a species only needs to "invest" in a single trait (either plumage OR song) to attract a mate and defend its territory. Although this has been tested in a many groups of birds, most studies have focused on smaller groups of species, and with conflicting results. The suboscines are a great group in which to test this idea, and we have been applying phylogenetic comparative methods to our song and plumage datasets to ask these questions.

Temporal dynamics of the transition to sympatry

The transition from allopatry to secondary sympatry following speciation is a central aspect to the buildup of species diversity. Speciation in birds is largely allopatric, in other words it takes place between geographically isolated populations. The ability of two species to co-exist (sympatry) after speciation is predicated on the two new species having diverged sufficiently in some aspect of their biology that allows them to either recognize one another as different species (divergence in signaling traits) or acquire resources differently (divergence in niche), or both. Both the time that it takes for species to come back into sympatry following speciation, and the amount of morphological divergence that is necessary to allow for that transition to sympatry are poorly known. My research aims to answer these questions in the suboscine passerine birds, a diverse group of species with the greatest diversity in the Neotropics. Along with a stellar group of collaborators, I have compiled data on geographic distributions, genetic data, song, plumage, and morphometrics for all suboscine birds. This project can be broadly divided into 1) the timing of the transition to sympatry and 2) the traits that mediate the transition to sympatry.

Some results on the timing of the transition to sympatry can be seen in my talk at the 2021 American Ornithological Society conference, below:

Note: includes captions in Spanish.

Most of my current research involves questions about macroevolution in the suboscine passerines. This is one of dominant groups of passerine birds in South America, where they have diversified into a wide variety of habitats, from deserts to rainforests, and from sea level to the highest mountains. They comprise about 1,300 species, and occupy a broad diversity of niches that are occupied by the oscine passerines elsewhere in the world. I am interested in how this diversity came about, both the diversity of species and the diversity of traits. In collaboration with researchers from many instituions I have compiled a species-level database of phylogenetic, distributional, song, plumage, morphometric, and ecological data from all species of suboscine passerine birds. This is an active area of research, and if this research interests you, either as a student or a collaborator, please reach out. Below, I have outlined two current research projects using these data, but there are many additional avenues of research that would be fruitful.

This work is in collaboration with the following researchers, and I encourage anyone interested in this topic to look into their research as well. Joseph Tobias at Imperial College London, Gustavo Bravo at the Instituto Alexander von Humboldt, Santiago Claramunt at the University of Toronto, Elizabeth Derryberry at the University of Tennessee Knoxville, Robb Brumfield at Louisiana State University, Rafael Marcondes at Rice University, and Michael Harvey at University of Texas El Paso.

Tradeoffs in sexually selected traits

As far back as Charles Darwin, researchers have noted that species of birds that sing complex or loud songs often have "dull" plumage, and vice versa. This idea is often termed the Transfer or the Trade-off Hypothesis, with the idea being that a species only needs to "invest" in a single trait (either plumage OR song) to attract a mate and defend its territory. Although this has been tested in a many groups of birds, most studies have focused on smaller groups of species, and with conflicting results. The suboscines are a great group in which to test this idea, and we have been applying phylogenetic comparative methods to our song and plumage datasets to ask these questions.

Temporal dynamics of the transition to sympatry

The transition from allopatry to secondary sympatry following speciation is a central aspect to the buildup of species diversity. Speciation in birds is largely allopatric, in other words it takes place between geographically isolated populations. The ability of two species to co-exist (sympatry) after speciation is predicated on the two new species having diverged sufficiently in some aspect of their biology that allows them to either recognize one another as different species (divergence in signaling traits) or acquire resources differently (divergence in niche), or both. Both the time that it takes for species to come back into sympatry following speciation, and the amount of morphological divergence that is necessary to allow for that transition to sympatry are poorly known. My research aims to answer these questions in the suboscine passerine birds, a diverse group of species with the greatest diversity in the Neotropics. Along with a stellar group of collaborators, I have compiled data on geographic distributions, genetic data, song, plumage, and morphometrics for all suboscine birds. This project can be broadly divided into 1) the timing of the transition to sympatry and 2) the traits that mediate the transition to sympatry.

Some results on the timing of the transition to sympatry can be seen in my talk at the 2021 American Ornithological Society conference, below:

Note: includes captions in Spanish.

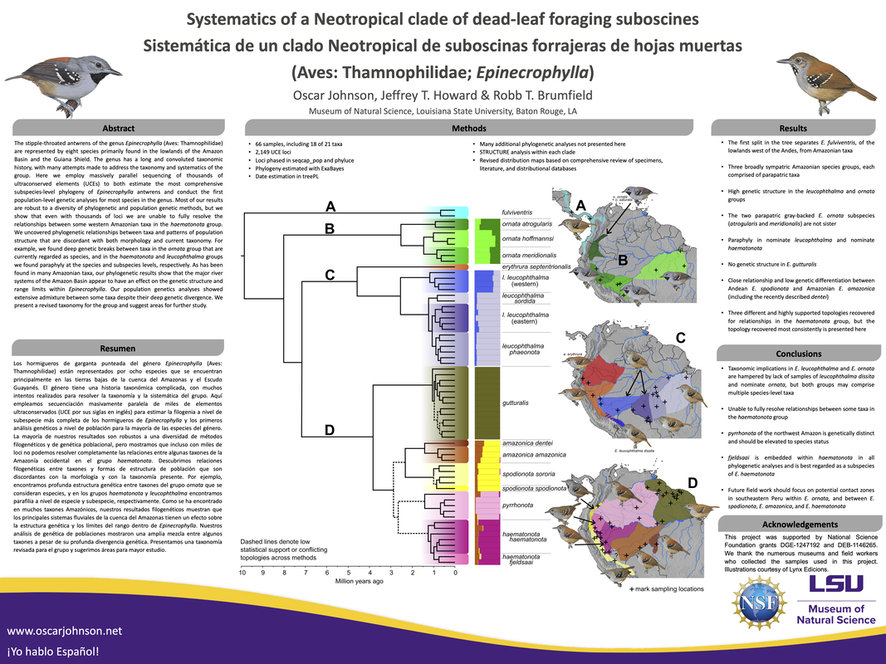

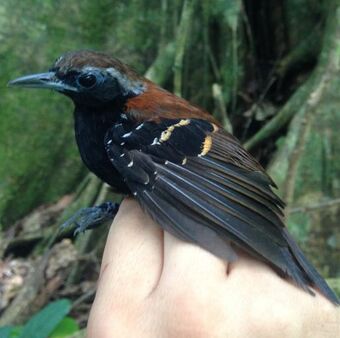

Epinecrophylla antwren systematics

The Neotropics hold a vast diversity of species for which there have been few or no phylogenetic studies using modern methods. Because of this, studies often reveal hidden diversity or evolutionary histories that are discordant with morphological analyses of relationships. This project focuses on one such group, the antwrens or stipplethroats in the genus Epinecrophylla. This genus has fairly conserved morphology, but there can be up to three sympatric species at a location. This, combined with its convoluted taxonomic history and multiple potential hybrid zones, makes it an interesting system to investigate with phylogenomic methods.

In August 2020 I presented a poster at the North American Ornithological Conference (NAOC) on the results of this study. This conference was held virtually, and was free to students. Both of these things helped increase attendance for students (especially in Latin American countries) who might not otherwise be able to travel to a large international conference, and was, I think, a great way to increase accessibility to researchers in these regions. I have included our poster below in the hopes that it reaches even more people.

This work is now published in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. See the Publications page for more details, or the paper here. There is still much work to be done on this group, including a comprehensive taxonomic revision, quantification of contact zones (especially in southern Peru), genetically unsampled taxa (including nominate E. ornata), and detailed analyses of plumage and song.

© Oscar Johnson

© Oscar Johnson

New species of antbird

In 2016 I had the honor of participating in a project to describe the Cordillera Azul Antbird as a species new to science. Published in 2018, we gave the bird the latin name of Myrmoderus eowilsoni in honor of the Myrmecologist and "father of biodiversity", Dr. E. O. Wilson. The species is currently known only from the type locality in the Cordillera Azul of northern Peru, but we hope that additional field work in the area will result in additional known localities for the species. This same mountain range is home to two other bird species described to science in the last 20 years, so hopefully more discoveries await!

You can read all about this discovery in the paper linked under the Publications page on this site. Popular press articles are available here and here. An account for this species has now been published (for subscribers) on Cornell's Birds of the World website, here.

Addendum: A recent preprint on bioRxiv titled "Global inequity scientific names and who they honor" has called attention to the use of eponyms for birds in the global South named by and for researchers in the global North. This manuscript used specific reference to Myrmoderus eowilsoni to illustrate this disparity. I feel that this is an important conversation to have and have posted a link to that manuscript here in order to hopefully foster conversation on this topic.

In 2016 I had the honor of participating in a project to describe the Cordillera Azul Antbird as a species new to science. Published in 2018, we gave the bird the latin name of Myrmoderus eowilsoni in honor of the Myrmecologist and "father of biodiversity", Dr. E. O. Wilson. The species is currently known only from the type locality in the Cordillera Azul of northern Peru, but we hope that additional field work in the area will result in additional known localities for the species. This same mountain range is home to two other bird species described to science in the last 20 years, so hopefully more discoveries await!

You can read all about this discovery in the paper linked under the Publications page on this site. Popular press articles are available here and here. An account for this species has now been published (for subscribers) on Cornell's Birds of the World website, here.

Addendum: A recent preprint on bioRxiv titled "Global inequity scientific names and who they honor" has called attention to the use of eponyms for birds in the global South named by and for researchers in the global North. This manuscript used specific reference to Myrmoderus eowilsoni to illustrate this disparity. I feel that this is an important conversation to have and have posted a link to that manuscript here in order to hopefully foster conversation on this topic.

© Wikipedia

© Wikipedia

River Island Phylogeography

One of my dissertation chapters focused on the comparative phylogenetics of river island bird specialist species in the Amazon Basin. This community of birds are restricted to scrub habitats on seasonally flooded islands in the Amazon and Orinoco Rivers and their major tributaries. The map of northern South America at right illustrates the highly linear distribution of this ecosystem. I am interested in how dispersal and high linearity of habitat affect gene flow and population structure in this system.

In collaboration with Camila Ribas at the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia and Alexandre Aleixo at the University of Helsinki, we recently published results from this work in Molecular Ecology. See the Publications page for more details.

One of my dissertation chapters focused on the comparative phylogenetics of river island bird specialist species in the Amazon Basin. This community of birds are restricted to scrub habitats on seasonally flooded islands in the Amazon and Orinoco Rivers and their major tributaries. The map of northern South America at right illustrates the highly linear distribution of this ecosystem. I am interested in how dispersal and high linearity of habitat affect gene flow and population structure in this system.

In collaboration with Camila Ribas at the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia and Alexandre Aleixo at the University of Helsinki, we recently published results from this work in Molecular Ecology. See the Publications page for more details.

Undergraduate Research

Golden-crowned Sparrow, © Oscar Johnson

Golden-crowned Sparrow, © Oscar Johnson

Social interactions in the Golden-crowned Sparrow

My undergraduate thesis focused on the flocking dynamics and long-term social interactions in the Golden-crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia atricapilla) in the lab of Dr. Bruce Lyon. Using a wintering population of color banded birds, we were able track individuals and associations between individuals on a small spacial scale. Using these data, and lead by Dr. Diazaburo Shizuka, we were able to show that individuals associate with each other more than expected by chance, and that these associations last across years. More information on this study is available on the Publications page on this site.

My undergraduate thesis focused on the flocking dynamics and long-term social interactions in the Golden-crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia atricapilla) in the lab of Dr. Bruce Lyon. Using a wintering population of color banded birds, we were able track individuals and associations between individuals on a small spacial scale. Using these data, and lead by Dr. Diazaburo Shizuka, we were able to show that individuals associate with each other more than expected by chance, and that these associations last across years. More information on this study is available on the Publications page on this site.

Natural History and distributional data

I strongly believe that natural history observations are an extremely important part of ornithological research. These publications often receive less attention that bigger and more well-funded research, but typically provide the foundation for much of that work. Additionally, bird distributions, particularly in the tropics, are relatively poorly known, and new discoveries are common. Below I have highlighted some of the recent natural history and fieldwork based publications that I have been involved in.

I strongly believe that natural history observations are an extremely important part of ornithological research. These publications often receive less attention that bigger and more well-funded research, but typically provide the foundation for much of that work. Additionally, bird distributions, particularly in the tropics, are relatively poorly known, and new discoveries are common. Below I have highlighted some of the recent natural history and fieldwork based publications that I have been involved in.

© Oscar Johnson

© Oscar Johnson

Nesting behavior of the Gray-mantled Wren

There are two species of arboreal wrens in the genus Odontorchilus and both are relatively poorly known. In 2016, while doing field work in the Cordillera Azul of Peru, I found a pair of Gray-mantled Wrens (Odontorchilus branickii) constructing a nest in the hollowed out base of a fallen palm frond. Upon returning to Baton Rouge and researching this species, I realized that there had been no published description of the nest of this species. While I was not able to access the nest that I observed for detailed observation, I published my observations such as they were, and described the nest in the context of the evolutionary history and nesting behavior related species. Hopefully someone else will be able to find more nests of this species and obtain a more detailed description!

There are two species of arboreal wrens in the genus Odontorchilus and both are relatively poorly known. In 2016, while doing field work in the Cordillera Azul of Peru, I found a pair of Gray-mantled Wrens (Odontorchilus branickii) constructing a nest in the hollowed out base of a fallen palm frond. Upon returning to Baton Rouge and researching this species, I realized that there had been no published description of the nest of this species. While I was not able to access the nest that I observed for detailed observation, I published my observations such as they were, and described the nest in the context of the evolutionary history and nesting behavior related species. Hopefully someone else will be able to find more nests of this species and obtain a more detailed description!

© Cristian Mur

© Cristian Mur

Field expeditions

Field work is an important part of my research, as a means of obtaining new samples for research, and as an opportunity for training, outreach, and discovery. I have been fortunate to do field work in many countries, both as part of my own research and in collaboration with many great scientists. My field work has focused on tropical and (more recently) montane desert habitats, including in Peru, Bolivia, Sumatra, Mexico, Equatorial Guinea, and the desert southwest of the United States. This work is closely tied to museum collections and all the specimens collected on these trips are deposited in publicly available collections for use by future researchers. The museums I have worked with include the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science (LSUMNS), Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI), Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Museo de Zoología "Alfonso L. Herrera". Museo de Historia Natural Noel Kempff Mercado, and the UTEP Biodiversity Collections.

Details on one of these expeditions, to the Río Huallaga, is outlined below:

In 2016, the LSUMNS led an ornithological expedition to the right bank of the lower Río Huallaga in the lowlands of northern Peru. This trip followed up on an LSUMNS expedition to the left bank of that river in 2001. Together, these expeditions were the first ornithological research done in the region since the late 19th and early 20th centuries! Those early expeditions described many new species of birds, but little work had been done since that time. In the nearly 60 field days that LSUMNS researchers spent in the field (of which I participated in about half) in the region, we documented range extensions for nine species, often by multiple hundreds of kilometers! It just goes to show how much more there is to learn in these remote regions of the Amazon. More details on this research can be found in our publication.

In keeping with our commitment to increasing representation of researchers in the countries in which we work, all of our field work was done in collaboration with Peruvian researchers at the Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) in 2016 and the Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (UNMSM) in 2001. Our field crew for the 2016 expedition is pictured above.

Field work is an important part of my research, as a means of obtaining new samples for research, and as an opportunity for training, outreach, and discovery. I have been fortunate to do field work in many countries, both as part of my own research and in collaboration with many great scientists. My field work has focused on tropical and (more recently) montane desert habitats, including in Peru, Bolivia, Sumatra, Mexico, Equatorial Guinea, and the desert southwest of the United States. This work is closely tied to museum collections and all the specimens collected on these trips are deposited in publicly available collections for use by future researchers. The museums I have worked with include the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science (LSUMNS), Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI), Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Museo de Zoología "Alfonso L. Herrera". Museo de Historia Natural Noel Kempff Mercado, and the UTEP Biodiversity Collections.

Details on one of these expeditions, to the Río Huallaga, is outlined below:

In 2016, the LSUMNS led an ornithological expedition to the right bank of the lower Río Huallaga in the lowlands of northern Peru. This trip followed up on an LSUMNS expedition to the left bank of that river in 2001. Together, these expeditions were the first ornithological research done in the region since the late 19th and early 20th centuries! Those early expeditions described many new species of birds, but little work had been done since that time. In the nearly 60 field days that LSUMNS researchers spent in the field (of which I participated in about half) in the region, we documented range extensions for nine species, often by multiple hundreds of kilometers! It just goes to show how much more there is to learn in these remote regions of the Amazon. More details on this research can be found in our publication.

In keeping with our commitment to increasing representation of researchers in the countries in which we work, all of our field work was done in collaboration with Peruvian researchers at the Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) in 2016 and the Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (UNMSM) in 2001. Our field crew for the 2016 expedition is pictured above.

© 2022 Oscar Johnson